22/01/2025 - Empowering Teachers, Inspiring Change: Ethics Education in Romania

In 2009, Laura Molnar returned to Romania full of enthusiasm after attending a training workshop in Geneva, Switzerland on a recently launched program called Learning to Live Together (LTLT). “This is exactly what I was looking for,” she thought and immediately began working to engage teachers in Bucharest to implement the program with their students.

At that time, Laura was working as a psychologist for children in vulnerable settings. Her work gave her insight into many cases of children in need of a resource that could help them nurture empathy, and respect, and develop better skills for resolving conflicts peacefully.

“A lot of children had deep traumas, significant emotional challenges, and struggled to control their anger. They came from disorganized families, faced discrimination, and lived in poverty. All of this created a sense that they were unequal to other children and didn’t deserve what others had.”

When Laura discovered Learning to Live Together, she felt like the manual had already existed in her mind, but she had never had the chance to put it into writing. “Fortunately, someone else did it for me,” she laughs. “LTLT was the structure I needed, and it was in line with the direction I was already heading,” Laura adds.

She returned to Romania brimming with energy and ready to spread her enthusiasm among teachers. However, rather than the receptivity she had hoped for, she encountered skepticism. However, Laura was convinced, and she began implementing the Learning to Live Together program with children.

In November 2009, Laura and a team of trainers organized the first Learning to Live Together workshop in Bucharest, introducing the manual to 26 teachers, social workers, theologians, and child protection authorities. That marked the beginning of years of encouraging teachers across Romania to use the program in their classrooms.

During visits to schools and interactions with educators, Laura and her colleagues discovered that, although teachers were indeed very busy—some even worked two jobs and had little time—they were also in need of resources to help them create more peaceful environments for their students.

Teachers were dealing with conflicts in their classrooms that they didn’t know how to address and felt unprepared to solve them effectively. “I am afraid when I see children furious and don’t know how to manage that… I notice I get involved, and I can’t stay neutral… I want to side with the victim,” Laura recalls some of the comments she received from teachers at the time.

One year later, in 2010, Laura was selected to participate in the International Train the Trainers course organized by Arigatou International Geneva, which led her to a certification as a Learning to Live Together trainer.

The program was still implemented on a very small scale. “People would argue that teachers wouldn’t have the resources, time, energy, or motivation to implement a program of this nature. This is when I realized that accrediting the LTLT course with the Ministry of Education was key to the success of my project,” recalls Laura. She was convinced that with the accreditation on the table, teachers who attend the course would gain credits that could help them advance their profession.”

She started the accreditation process by doing some research. She developed a questionnaire for teachers and applied it in different parts of the country. The results showed that ethics education was one of the main learning needs among teachers. With this information on hand, Laura elaborated the first curriculum of the training course, in accordance with the requirements of the Ministry of Education.

“It took a couple of months to prepare the accreditation file and a few more to get an answer from the Ministry. Finally, the letter came. We got the accreditation and we were ready to start the courses,” she recalls. Soon enough, with the support of Lucreția Baluță, Coordinator of UNESCO Associated Schools in Romania, the manual was translated into Romanian, and dozens of teachers were trained. But the real challenge was just beginning.

“I realized that even if I convinced the teachers to stay in the course, most of them kept the learnings as a resource for their personal development, but didn’t apply it in their classrooms,” Laura says.

Andreea Vasile shares a similar experience. She is a psychologist who has been implementing the Learning to Live Together program for many years. As she recalls, teachers often felt it was difficult to generate ethical dialogues among students. Some even thought that by establishing a horizontal discussion, they would lose their authority in front of the children. Andreea, who has been supporting Laura in spreading the program across Romania since 2015, reflects on this perception.

Having teachers interested in attending the courses wasn’t enough. Laura and her team needed to do more if they truly wanted to see the program implemented systematically in formal education across Romania. That’s when they developed a very effective strategy, one they still use today.

“We created a mentoring program and a community of practice, where teachers could see and learn from the experiences and achievements of their colleagues,” says Andreea.

Once a month, teachers in the mentoring program have the opportunity to host a member of Laura’s team, who conducts a Learning to Live Together session with their students. Observing an experienced facilitator running the workshop helps teachers familiarize themselves with the program and methodology, building their confidence to lead the next sessions until the facilitator visits again the following month.

The system turned out to be a success. “We’ve had sessions with up to 70 teachers supported by the mentoring program,” says Laura, who still dedicates many hours a week to conducting these support sessions. She admits that it can be tiring, but it’s worth it: “This way, it’s easier for us to monitor the implementation and see the children’s progress.”

And seeing the children’s progress is certainly the most rewarding part of the work. Every now and then, Laura likes to check Facebook to see what’s going on with the lives of the children who participated in the program during its early years. Ten years later, those children are now young adults. “I am so proud to see them. Almost all of them have beautiful families now. I love the way they speak, how they treat their children, and how much they care about them… Some work abroad and have very nice jobs, and for sure…” Laura pauses here to laugh, “…even better salaries than us,” she chuckles.

Laura laughs because she knows that the driving force behind dedicated trainers like her and Andreea is not a salary, but the opportunity to make a meaningful impact on children’s lives. As Andreea says, “If I had to sum up my approach in one sentence, I’d quote Gandhi: ‘Be the change that you wish to see in the world.'”

For children, this change has meant a more peaceful learning environment, a better ability to express themselves and resolve conflicts non-violently, and greater empathy and sensitivity toward others’ needs. As one teacher and LTLT facilitator puts it: “Students are more attentive, more reflective, and even more self-critical in a constructive way… they’ve become more open-hearted and open-minded,” says Eryka Lang, a teacher at Aletheea School, in a video recorded in 2018 in Bucharest.

Aletheea School, which opened in 2014, has integrated several elements of the Learning to Live Together program into its curriculum. Teachers and students are familiar with resources like the learning logs, and the program’s methodology is consistently incorporated into the school’s pedagogical approach. “They have a very horizontal way of teaching,” says Andreea.

Aletheea School’s commitment to Learning to Live Together is just one example of the program’s impact in Romania, thanks to Laura and her team’s dedication. “There are so many teachers involved now that no one questions whether they should trust me in this mentoring program,” says Laura. Andreea agrees: “I even tell Laura that we should multiply ourselves. We’re four trainers right now, but it feels like we’re ten,” she laughs.

In 2019, Arigatou International started the adaptation of the Learning to Live Together manual for children aged 6 to 11, expanding its reach beyond the original 12 to 18 age group. As part of this global effort, Laura supported the process in Romania, organizing and facilitating pilot sessions to test and refine the adaptation.

One of these pilots took place in Bucharest on April 17–18, 2019, in collaboration with the Education for Change Association, Kids Palace School, and GNRC – Romania. A diverse group of 29 children from Buddhist, Christian, and Muslim backgrounds, as well as Belgian, Chinese, Romanian, Roma, and Turkish heritage, explored values of respect, empathy, and coexistence. Reflecting on the experience, a 10-year-old participant shared, “I learned that when we have different opinions, we have to respect them and not judge others. And that we must help people in need.”

Gone are the days when Laura had to knock on doors, trying to convince teachers that the program would help them address conflict in their classrooms and create peaceful environments for their students. “Now we don’t need to promote LTLT. Teachers speak to each other, and we get calls from schools,” Laura says, adding that she and Andreea have recently created their own organization to focus more on their work with the Learning to Live Together program, along with other initiatives for children’s well-being.

Today, schools in six different regions of the country are engaged in varying levels of the program, fostering values of empathy, respect, responsibility, and reconciliation in their students. More than ten years of dedicated work have resulted in more than 2,000 teachers trained, with 250 teachers directly involved in the program and more than 10,000 children reached.

Thanks to the commitment of trainers and facilitators like Laura Molnar, Andreea Vasile, Eryka Lang, Papuc Ileana, Oprea Diana, Any Ureche, Luciana Sidor and many others, the program will continue to reach children in more schools across Romania.

The post Empowering Teachers, Inspiring Change: Ethics Education in Romania appeared first on Ethics Education for Children.

22/01/2025 - From Classrooms to Communities: Scaling Ethics Education Nationwide in Kenya

Tana River County in southeastern Kenya is an emblem of diversity and resilience. Endowed with natural resources, it has endless potential, but the harsh weather conditions test the strength of its people daily. The land swings between extremes—erratic rainfall with upstream floods one season, and relentless drought and water scarcity the next. These conditions often spark tensions among communities. Yet, amid these challenges, there is a remarkable effort to bring transformation through the power of education.

Over the years, violence has brought chaos to Tana River County affecting communities, families, and even schools. In August 2012, the region witnessed one of the worst violent conflicts in its history; as a result, 200 people, mostly women and children, were killed due to clashes between the two main ethnic groups, the Pokomo and the Orma.

The Pokomo are settled farming people while the Orma are mainly cattle-herding pastoralists. Both groups have a long history of tension over access to land and water in this ecologically rich area.

Against this challenging backdrop, a truly heartwarming moment unfolded in September 2015. The very children and teachers who, just a few years earlier, struggled to even speak to one another were now coming together—learning, dancing, and sharing stories in harmony. In a powerful celebration of unity, more than 200 children from the Pokomo, the Orma, and several other ethnic groups gathered to commemorate the International Day of Peace, proving that education and understanding can bridge even the deepest divides.

This celebration did not happen by chance—it was the result of several collective efforts, dialogue, and collaboration. It all began when Mary Kangethe first encountered Arigatou International and its transformative Learning to Live Together (LTLT) program. At the time, Mary was serving as Assistant Director of Education at Kenya’s Ministry of Education, and she immediately recognized the program’s potential to make a lasting impact. Determined to bring it to Kenya, she joined a Training Workshop in 2014, where she became a certified Facilitator.

The Learning to Live Together program was then introduced to the Ministry of Education of Kenya. Soon enough, the Ministry partnered with Arigatou International and the UNESCO Regional Office for Eastern Africa to develop a program to address the need for mutual coexistence in the community through education. Together, they worked to adapt the principles of the Learning to Live Together program to the Kenyan context, integrating ethics and values-based education into the national curriculum.

“We were already implementing programs in Tana River (…) we had done a psychosocial intervention there,” remembers Mary. She candidly admits that when they got to know about Learning to Live Together, “we thought ‘Okay, this is just another program.’” However, in-depth exploration of the manual allowed them to identify “several gaps in our peace education programs, in terms of how we promoted values and concretely engaged teachers, and therefore we were open to pilot an intervention.”

But for the intervention to succeed, they had to start from the ground up—building capacity within the Ministry of Education to ensure teachers in Tana River County received the training, support, and follow-up needed to effectively implement the Learning to Live Together program in their schools.

In September 2014, 15 Ministry officers participated in an intensive four-day workshop, equipping them with the knowledge and skills to take on this challenge. With this foundation in place, they went on to train 25 teachers, guiding them in how to use the Learning to Live Together manual, its framework and approach, and develop essential facilitation skills. The teachers were strategically selected from the areas most affected by violence. Two teachers from each of these schools—one male and one female—were trained to lead the way.

The workshop saw a slow and cautious process of allowing teachers to open up and build bridges of trust. Julius Waweru Ng’ang’a, from the Ministry of Education, who at the time was District Quality Standards Officer of Tana Delta, recalls: “As the training progressed, the teachers started mingling and communicating.” Before long, the change in their attitude was noticeable, “even in the way of dressing, in the level of confidence, and the capacity to express themselves,” says Mary.

In the end, the teachers were trained as facilitators throughout three basic training workshops. “We felt excited to see them progressing, but also aware that they still required a lot of support,” says Mary.

To this point, they seemed to have everything: the manual, the confidence, the training, and yet something was still missing. “We realized that it was a big challenge for the teachers to come up with a lesson plan from the manual and deliver it”, admits Mary. That is when the Kenyan officers took a step forward: “We agreed that we were going to develop a teachers’ activity book that would customize the LTLT manual to the Kenyan context.”

With a solid pedagogical foundation in place, teachers implemented customized Learning to Live Together programs in their schools from February to July 2015. Their efforts extended beyond the classroom, as from June to August 2015, they facilitated child-led initiatives aimed at transforming mindsets within schools and the broader community. “Teachers planned and organized activities that encouraged children, teachers, and school communities to think differently,” explains Julius. “Many even took children into the villages to engage directly with community members, raising awareness and inspiring change.”

The impact of these initiatives was profound. “Children became deeply connected,” recalls Mary. “We saw their confidence, creativity, and enthusiasm grow. I remember one school that developed an intervention to prevent child marriage, and they even managed to rescue a girl who had already been married.”

By September 2015, the International Day of Peace event marked the successful completion of the pilot program in Tana River County, having reached 657 children. The program left a lasting impact, fostering positive outcomes such as improved conflict resolution skills, greater confidence in sharing and participating in lessons, and a renewed motivation to attend school.

However, the pilot program not only resonated in the communities and the county, but it also expanded at the national level through policy-making processes. “We escalated it to the curriculum reform, so those principles can be mainstreamed and implemented in schools (across the country)”, says Mary, pointing out that this is probably the most important outcome of the whole experience.

The journey that began in Tana River County grew into a nationwide movement, shaping the future of ethics education in Kenya. Arigatou International supported the curriculum review process, particularly the development of the values-based education curriculum, a consultative process that allowed the country to reflect and formulate how the education system can foster ethical values that promote peace and social cohesion.

The experience with the Learning to Live Together program, the training of teachers, the training of education personnel from the Ministry as well of Curriculum Developers was pivotal for this effort. “The nurturing of values will facilitate the achievement of the curriculum reforms’ vision, particularly with respect to molding ethical citizens. Curriculum is used as a channel through which ethics education can be enhanced for sustainable peace in the world” said Jane Nyaga, former Assistant Director of the Kenya Institute for Curriculum Development.

In 2017, Mary’s passion and commitment to advancing ethics education earned her a place in the International Training of Trainers in France—an experience that solidified her role as a Learning to Live Together Trainer. That same year, she started working as Director of Education Programs at the Kenya National Commission for UNESCO (KNATCOM).

Following the success in Tana River, in 2023, the Ministry of Education of Kenya embarked on a new and ambitious initiative—the Ethics Education Fellowship. This groundbreaking program has successfully expanded across Bangladesh, Indonesia, Kenya, Mauritius, Nepal, and Seychelles, strengthening ethics education in formal school settings and fostering global citizenship.

The Fellowship is made possible through a partnership between the Ministries of Education of each country with Arigatou International, the Guerrand-Hermes Foundation for Peace, KAICIID International Dialogue Centre, the Muslim Council of Elders, the Higher Committee of Human Fraternity, the UNESCO New Delhi Cluster Office, and the UNESCO Regional Office for Eastern Africa, in collaboration with the National Commissions for UNESCO of the participating countries.

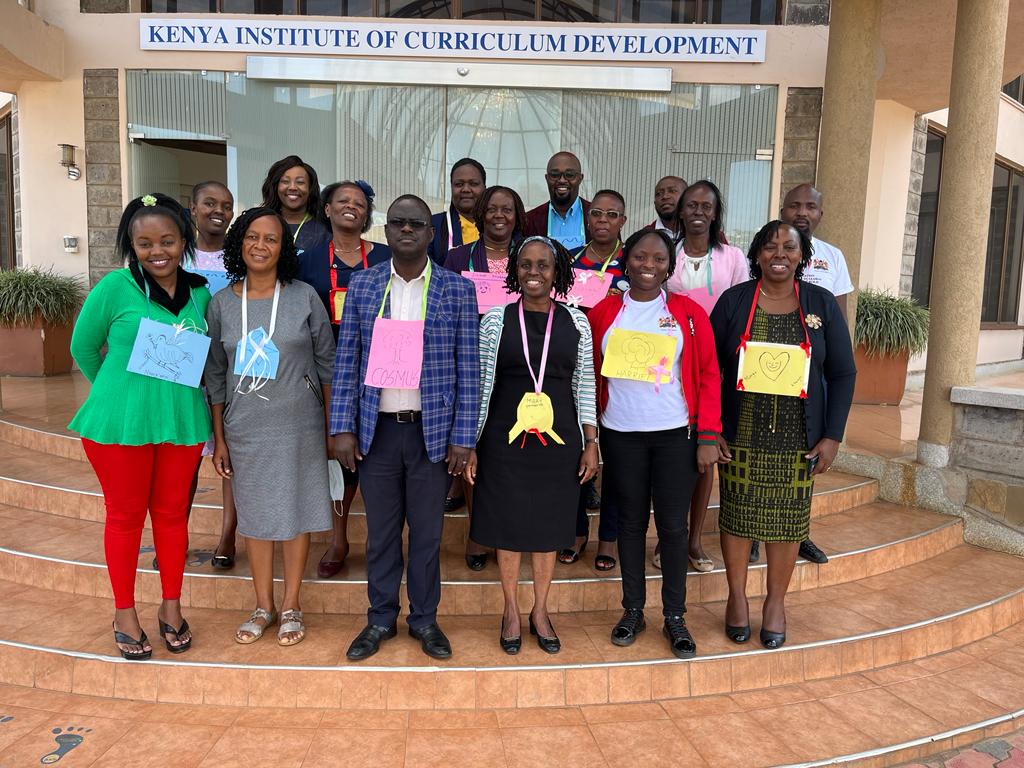

In Kenya, the pilot was a collaboration between the Ministry of Education and the quality assurance office, Kenya Institute of Curriculum Development (KICD), Kenyatta University and Thogoto Teacher Training College. The program also engaged high-level stakeholders, including Africa Nazarene University and KNATCOM, with Mary at the forefront of the education programs.

The five fellows from Kenya trained 32 schoolteachers and eight teacher trainers, who in turn empowered students with essential skills for peacebuilding and conflict resolution. The program ran from March to August 2023, reaching 1,620 learners.

The impact has been transformative: 72% of learners reported they could form friendships with people from different backgrounds, and 77% felt more confident in listening and understanding others’ perspectives. “At the beginning, I didn’t know how to interact with others because of my skin color, but the program helped me,” reflected a student.

Students launched child-led initiatives like Peace Gardens and Talking Walls to address issues such as bullying and climate change, demonstrating their commitment to creating a more inclusive and compassionate world.

“Through participatory and collaborative learning, students who were once hesitant to ask questions now feel comfortable seeking assistance from their peers. I’ve also learned the importance of creating a safe learning environment, resulting in my students eagerly anticipating my lessons,” shared one teacher.

As Kenya moves into Phase Two of the Fellowship program in 2025, the goal is to strengthen and expand its reach, ensuring that more children and educators benefit from the transformative power of ethics education and that more teachers get trained through in-service and pre-service training programs.

“Our fellows will continue working together as a cohesive team. We have discovered valuable synergies, having come from diverse areas within the education sector. These synergies are proving to be highly effective in driving the successful implementation of ethics education across the country,” remarked Mary, reflecting on the second phase of the program.

What began as a small pilot has evolved into a national effort—one that is shaping a generation of compassionate, empathetic, and responsible citizens. Mary has been instrumental in this transformative journey. The future of ethics education in Kenya is bright, and this is just the beginning.

Education provides a major opportunity to facilitate the development of competencies for the prevention of violence and for promoting peaceful coexistence. This includes critical thinking, negotiation, problem-solving, and decision-making skills.

The post From Classrooms to Communities: Scaling Ethics Education Nationwide in Kenya appeared first on Ethics Education for Children.

17/01/2025 - Shaping the Next Generation of Young Leaders With The Power of Empathy

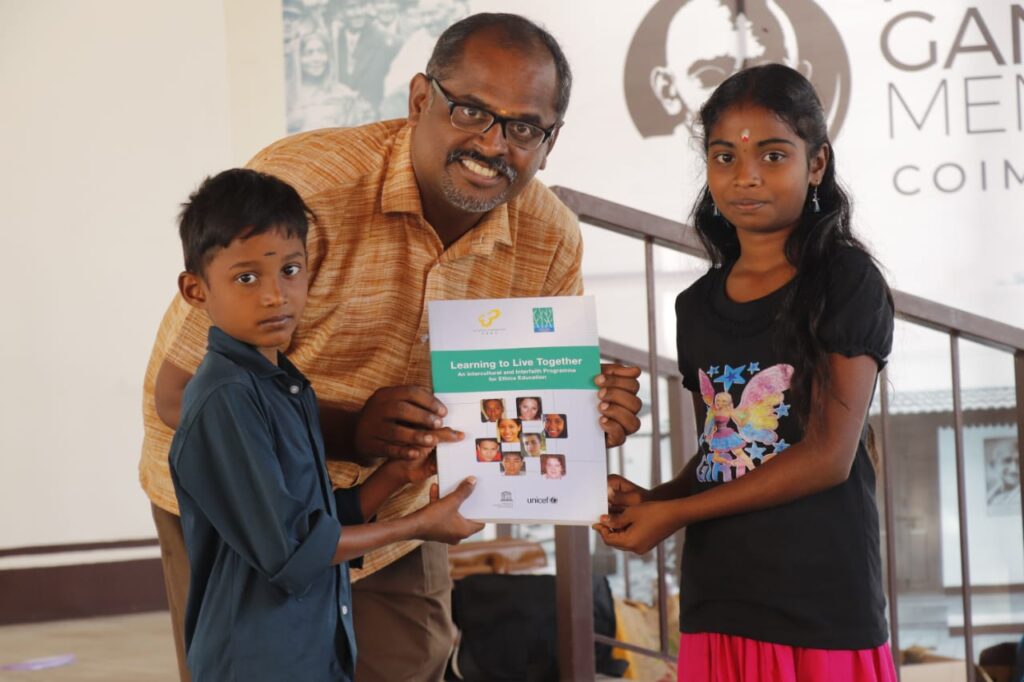

Shanti Ashram is a creative laboratory that addresses local issues and provides constructive solutions for communities in Coimbatore, India. With a team of only 40 members, the organization has managed to reach 250,000 people all around Coimbatore and some other areas of India. How has Shanti Ashram achieved such an impact?

If presented with this question, Vijayaraghavan Gopal (or simply Vijay, as his friends like to call him) would probably say that everything Shanti Ashram has built is based on the power of empathy. “Without our volunteers, we couldn’t do anything (…) With only 40 people in Shanti Ashram is impossible to reach 100,000 children every year”, says Vijay who is constantly encouraging and inspiring the 200 volunteers that support the work of the organization.

Certainly, among the four values highlighted in the Learning to Live Together manual, empathy stands out as the one Vijay finds most powerful. And if there’s one thing Vijay knows inside and out, it’s the Learning to Live Together manual.

“You’ll always find the manual on my desk,” admits Vijay, who has been with Shanti Ashram for over 20 years. For more than half of that time, he has relied on the Learning to Live Together program to support his work.

Shanti Ashram, a partner of Arigatou International since 2000, is likely the organization that has been integrating Learning to Live Together for longer than any other worldwide.

“Before we used to call it Ethics Education toolkit”, explains Vijay remembering the times back in 2006 when Shanti Ashram was already working with Arigatou International in implementing ethics education programs, that would later become the structure for what is now Learning to Live Together.

Shanti Ashram was established in 1986, following the principle of Mahatma Gandhi of “Sardovaya” or “welfare/progress for all”. Since then, the organization has been carrying out numerous projects to assist vulnerable people in Coimbatore, with an emphasis on education. They focus their action on three programs: a sustainable development program, a program to foster youth leadership (headed by Vijay), and an education program with the “Bala Shanti program”, or “places of peace for children”.

The Balashanti Kendras is an early childhood development program for vulnerable children ages 3 to 5. “We have 8 of these centers, with 25 children studying in each center. The uniqueness of our schools is that we offer ethics and value-based education. We work with the Montessori method in a Gandhian way,” explains Vijay.

Each Balashanti Kendra is managed by a single teacher, and all teachers across the eight centers have received training in the Learning to Live Together (LTLT) program. “We conduct workshops for all our teachers,” explains Vijay. “These workshops equip teachers with the knowledge to create safe and supportive learning environments, foster critical thinking and self-driven learning, and incorporate the values of respect, empathy, responsibility, and reconciliation into their teaching.”

Since 2024, Shanti Ashram integrated a new program into its Bala Shanti program: Toolkit to Nurture the Spiritual Development of Children in the Early Years. This groundbreaking initiative, developed by the Consortium on Nurturing Values and Spirituality in Early Childhood for the Prevention of Violence, has brought about meaningful transformations among parents and caregivers. It supports children’s holistic development while fostering nurturing and respectful family environments.

The Bala Shanti educators are implementing the Toolkit directly with children. Additionally, 171 parents and caregivers participated in educational sessions. These sessions focused on child rights, the creation of safe environments, and strategies to enhance children’s agency, as well as their social and emotional development.

But Shanti Ashram is not only using the LTLT manual to train teachers, they use it in their programs to strengthen families, they use it during their summer camps for children and youth, they use it in workshops for volunteers, on workshops with young leaders, for activities with parents.

“Learning to Live Together is an incredibly flexible tool. We can adapt it to a wide range of activities—for instance, short sessions, one-day workshops, observation visits for undergraduate and postgraduate students, and social immersion programs for school children. It can also be integrated into any type of training program,” shares Vijay, proudly highlighting that Shanti Ashram has the highest number of international trainers for the Learning to Live Together program.

“Here in India, we have four international trainers—myself, Pavithra Rajagopalan, Prabha Karthik, and Kavya Balguruswamy—along with 220 facilitators. These young facilitators play a vital role in helping us conduct LTLT programs, reaching and engaging with diverse groups across different settings.”

After all these years of adapting and implementing the program, Vijay and his colleagues have harvested many fulfilling stories of how their work has impacted the lives of people in the community.

As Prabha Karthik, international trainer and Montessori teacher, said in an interview in 2015 “The best part of our work is that we create a space for (people) to learn, think, discuss and thrash out their own ideas.”

In 2015, with support from Shanti Ashram, Prabha and Pavithra customized the Learning to Live Together manual to develop a 10-month program to strengthen parenting skills. Prabha recalls deeply emotional moments from the workshops. One mother, for instance, shared her transformative journey: “She had a child with autism and initially believed she was being punished by having a child with challenges. However, through the program, she began to see her son as an individual in his own right, rather than simply as someone who belonged to her.”

Prabha acknowledges that the program had a profound impact on her as well. “It helped me realize that while we all love the children under our care, we are often constrained by our own conditioning and upbringing,” she reflects. “We rarely pause to think deeply about our actions in daily life. Many of us see our children as extensions of ourselves, as our property, and focus on raising them to reflect well on us, rather than embracing them as individuals with their own paths to follow.”

One of Shanti Ashram’s greatest strengths lies in its approach to children. The organization actively promotes a horizontal dialogue between adults and children, demonstrating a steadfast commitment to empowering its younger members and volunteers by giving them meaningful leadership roles. Despite her demanding schedule, Shanti Ashram’s director, Kezevino Aram, makes a conscious effort to be available for any child seeking her guidance. “They are even welcome to come to her house,” shares Vijay, highlighting her dedication to nurturing connections with the younger generation.

As children engage in the Learning to Live Together (LTLT) program, the ultimate goal is for them to become catalysts for positive change in their communities, working in collaboration with adults. The program actively fosters child-led initiatives, and Arun’s story is a powerful testament to its impact.

At just 14 years old, Arun was inspired after attending an LTLT workshop at Shanti Ashram to take action for those in need. Determined to make a difference, he initiated a food bank by collecting rice for vulnerable families—an effort that would go on to transform the lives of thousands in Coimbatore.

“After the program, he came to me and said, ‘Uncle, I want to do something for people,’” recalls Vijay. “He had the idea of collecting rice, and I encouraged it.” With support from Shanti Ashram, Arun’s project grew rapidly. Today, the food bank collects and distributes between 450 and 500 kilograms of rice, dhal, and other essential goods every month.

In 2019, this initiative received global recognition when it was awarded the Most Inspiring Child-Led Project by Arigatou International. The success of Arun’s food bank also inspired the launch of the India Poverty Solutions program in 2012—an innovative, child-led initiative dedicated to ending child poverty. Today, India Poverty Solutions has been replicated in four other countries, expanding its reach and impact far beyond its origins.

Now approaching 30, Arun continues to manage the food bank and remains actively involved in Shanti Ashram’s initiatives. Having dedicated half his life to volunteering with the organization, he is just one of many individuals who have remained deeply committed to Shanti Ashram’s mission, ensuring that its work continues to inspire and empower new generations.

“Sustainability is the key,” explains Vijay when describing how Shanti Ashram maintains volunteer engagement and keeps young people actively involved. “It’s a long and continuous process. It’s not about immediately getting children on board but about consistently providing opportunities for them. We create spaces for them to act as young facilitators and ensure there’s always room for motivation.”

Driven by empathy, the staff and volunteers of Shanti Ashram are doing more than supporting vulnerable individuals in Coimbatore—they are shaping a new generation of young leaders. These leaders are not only empowered to drive positive change in their communities but are also equipped with the values and skills to help build a more compassionate and inclusive world.

Shanti Ashram upholds the wisdom of Mahatma Gandhi, who famously said, “If we are to teach real peace in this world, we shall have to begin with the children.” This belief continues to guide their efforts, ensuring that education and values-based learning remain at the heart of their mission.

The post Shaping the Next Generation of Young Leaders With The Power of Empathy appeared first on Ethics Education for Children.

09/12/2020 - Restoring and Empowering Communities in Uganda Through Interfaith Learning and Collaboration

Ms. Nageeba Hassan has been at the forefront of the implementation and training on the Learning to Live Together Programme in Uganda, reaching children, parents, and teachers through Restoring and Empowering Communities (REC), an organization that she co-founded in 2004.

A teacher by profession, she has expertise in the fields of counseling, positive parenting, meditation, negotiation, interreligious dialogue, and intercultural learning. Her hard work and passion have taken her to many countries, training teachers and educators on ethics education for children, and speaking about interfaith collaboration. Her persistency and drive have helped her make real changes in the lives of many children in Uganda, their families, and their communities.

Ms. Hassan is a Learning to Live Together Trainer, a KAICIID Fellow, and a member of the African Woman of Faith Network, the International Woman Coordinating Committee of Religions for Peace, and the Women of Faith in Uganda.

Learn more about her journey in the following interview.

- Tell us about you, and your story.

I was born a Muslim and I love and practice my religion. At the same time, I peacefully co-exist with everyone. Both my parents passed on (May Allah grant them the best Janah). I have lived in 4 districts of Uganda (Iganga, Jinja, Kampala, and Wakiso) but I have been to most parts of the country. Uganda is in East Africa and borders DRC, South Sudan, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Kenya. The ‘Pearl of Africa’ is a must-visit country with good hospitable people.

My mummy, my inspiration in everything I do, didn’t go to school but wanted and supported my education. My dad, on the other hand, didn’t believe in girls going to school because they are supposed to get married to rich men and get pampered. I don’t blame my dad, that’s what he believed in culturally.

I had to go to a school away from home and lived with my uncle and his family for 5 years. He believed in corporal punishment and would beat us frequently. I once told my mother and she talked to him, but when she left he beat me for telling her, so I didn’t report again until after I left his home. The cane marks were very visible so I decided to wear long stockings and sweaters or jackets to cover them. That way I didn’t have to give explanations. This went on long after leaving his home thinking the cane marks were still showing (psychologically I felt them). I forgave him.

My mother was very sad when I told her about my life at my uncle’s place. She said I should have told her because she had promised that if I was beaten again she would take me back home and to another school. I guess I have turned childhood challenges into opportunities. That’s one of the reasons I founded Restoring and Empowering communities (REC) as a community-based organization (CBO) based on voluntary service in 2004. Together with friends and family, we reached out in different ways to communities. In 2014 we registered REC as a CBO and later we upgraded it to a non-government organization (NGO).

- Thank you for sharing about those difficult times, and how you turned that experience into an opportunity to helping others. Tell us about your journey with ethics education. How did you get to know Arigatou International?

I went to University to get a degree in Education and later a master’s in Peace and Conflict Studies at Makerere University. In between, I received several certificates and fellowships in all the fields I enjoy working in. The one I appreciate the most is my certificate on ethics education for children

I taught at the Aga Khan Primary School with a child-centered approach for 8 years and then started doing community work with children, parents, and teachers on positive parenting to prevent HIV/AIDS.

I moved into the religious circles and worked with the Muslim community through the Uganda Muslim Supreme Council (UMSC). There, with the support of grand mufti Shk. Shaban Ramadhan Mubaje and the Secretary-General Shk. Engineer Siraji Zaid Kavuma I formed the Muslim Women’s Desk, the first women structure that would work alongside that of men, which was finally promoted to a full department.

Later in the Interreligious Council of Uganda, working closely with the strongest team of women of faith -Sister Goretti Kisakye (RIP), Ms. Sarah Kasule (RIP), Ms. Florence Kwesigabo, Ms. Despina Namwembe, Ms. Gladys Nalubega, Ms. Esther Nakisige, Ms. Rose Ssegujja, Ms. Aisha Ssemakula, Ms. Mariam Naava and Ms. Hafswa Mutebi) with the full support of the Secretary-General Dr. Kitakule Joshua and the top religious leaders, we formed the National Coordinating Committee that I have chaired from 2014-2019 (UWOFNET). Currently, I’m one of the regional coordinators for the African Women of faith network with the African Council of religious leaders (AWFN-ACRL) and I seat on the International women coordinating committee with Religions for Peace (IWCC-RfP)

In 2013 I was invited to participate in the 9th World Assembly for Religions for Peace International that was hosted by KAICIID in Vienna. It was there where I first heard of Arigatou International and their work for children. I was very interested in it and I reached out to Dr. Mustafa Ali. The following year I was invited to Nairobi for a basic training workshop in ethics education for children, using the Learning to Live Together Programme. Learning to Live Together is like a holy book in all my work. I have since been trained as a Trainer in France and I was lucky to be trained online on the Ethics Education Approach, Building Safe and Inclusive Learning Environments for Children, and Monitoring and Evaluation. I also took part in the recent training for teachers to respond better during lockdown situations and school closures.

I co-facilitated Learning to Live Together workshops with other international Trainers in Mauritius for teachers and lecturers, in Tanzania for teachers working in Peace Clubs, and in Kenya for educators, managers and planners working at the Kenya Institute of Curriculum Development.

I have since integrated Learning to Live Together in all my work in schools. The children from the Book Club that I’m guiding, over time and practice, have been encouraged to come up with their own initiatives to address different issues in their schools. We have carried out campaigns on antibullying and hygiene among others. We also organized intergenerational dialogues with adults and stakeholders including teachers, parents, government officials, religious, cultural and opinion leaders, and elders on issues that concern them like child abuse especially corporal punishment and child sexual abuse and exploitation. We have been able to reach out to over 30,000 children directly and much more indirectly. This has been supported by Arigatou international, the schools themselves, Niteo Africa Society, KAICIID Dialogue Center and the Embassy of the United States.

We have carried out workshops on the Ethics Education Approach to help find alternatives to corporal punishment, and promote child-friendly methods of teaching, child protection, and basic counseling. We have worked with over 2,000 teachers in 70 schools supported mainly by the schools themselves.

The children in my country, like most children around the world, face challenges and abuse ranging from physical, sexual and emotional abuse. In this time, I have been able to work mostly around prevention, referral and psycho-social support. Children have dropped out of school due to different reasons like abuse both at school and home, poverty and parental neglect. We have child-headed families and many vulnerable children who have been forced into child labor, child marriages, and child trafficking among others. We work with parents, guardians, teachers, elders, and leaders to build safe environments for children.

- What challenges have you faced while working with children in vulnerable contexts?

Like any work, there are some challenges that we face especially in informal education.

In my country, teachers take the exam-oriented approach to finish the syllabus. This cuts back on any extracurricular activities. As a stand-alone program, it can be hard to have a buy-in unless one has established a long-term relationship with the school, and even so, sometimes the management changes, and the new team scraps off all that was built.

- ¿Do you have any advice for those trying to carry our programs based on Learning to Live Together?

My advice is using the Learning to Live Together Programme to have a long-lasting impact on topics like child protection, child abuse and exploitation, peacebuilding, prevention of violent extremism, poverty, harmful cultural rituals, civic education, solidarity, environment, life planning skills, positive parenting and learning for life among others. If we manage to integrate ethics across all the thematic areas, you will enjoy your work and get maximum results. Make ethics education your core in anything to be done, put it on the dialogue table, and get buy-in for it.

Funding is critical. We need to partner with schools and parents. Involve and engage them so they are aware of what’s happening at all times and they will fully support the children. Get their consent for different sessions that you feel will need to share photos and or have children participate outside the school or will involve people from other schools and organizations. Consent protects the children, you, and everyone. From our feedback, both parents and schools are impressed and appreciate how the children changed in behavior, attitude, and above all improved performance at school.

Ethics education is very important in everyone’s life and I strongly believe that if we all had it in our school’s curriculum, the world would be different today. Ethics education gives meaning to the term lifelong learning. The approach used allows growth, continuous learning, and helping others around you. Today the schools are exam-oriented with crush programs to complete syllabuses. The ethics education approach is an excellent tool to facilitate learning because it’s not only child-centered learning but engages the teacher and children right from the start. Children who are lucky to have ethics education have greatly improved their performance in academics and interpersonal skills. It allows the children to inquire, question, reflect, dialogue and think critically.

Ethics education calls for a good role model who motivates children to learn more, even if it is on their own, and moves them to understand themselves in relation to others and see themselves in the bigger picture of their communities. Ethics education gives spaces for peer learning and encourages collaboration towards a common concern as a collective responsibility to transform their communities. Children have the opportunity to learn how to be more empathetic, respectful, responsible and that can find reconciliation in nonviolent ways. Ethics education helps both adults and children to grow as individuals and live more ethically as a group, family, or community. The children are in a better position to make informed decisions and this will help them to prevent any form of injustices around them as children and later as leaders because they have the skill to reflect and think more critically.

Currently, with the pandemic and the schools being closed, we have changed our operation area to families, working closely with local leadership and Town Council Officials. We have a child/youth-led initiative that we have called Caring Communities. Through Caring Communities, children have mobilized 70 homes with 220 children and youths. We fundraised through a book sale, to build a safe space to offer free services to the community. ¡We got a good response!

Ms. Hassan and the children from Caring Communities have been working together throughout the COVID-19 Pandemic. They have raised funds to provide a safe space for their community to receive help, engage in dialogue with local authorities, and participate in workshops. They have carried out informative sessions to educate families on the hygiene measures required to prevent the spread of the virus and provided food and essential hygiene products. Also, Ms. Hassan has been able to carry out workshops on ethics education with a focus on empowering youth and fostering their participation.

We thank Ms. Hassan for working together with Arigatou International with such drive and passion, and her commitment to furthering children’s rights and wellbeing. We admire her groundbreaking work in interfaith learning and collaboration, in contexts where prejudice and divides were hindering dialogue and partnerships. She is a role model to many children and youth in her community, and an inspiration for all those working to build a better world for children.

The post Restoring and Empowering Communities in Uganda Through Interfaith Learning and Collaboration appeared first on Ethics Education for Children.

30/04/2020 - Countering Segregation Through Values-based Education in Bosnia and Herzegovina

Since 2011, the Learning to Live Together (LTLT) Programme has been making headway in Bosnia and Herzegovina under the leadership of Ms. Ismeta Salihspahić, local GNRC Coordinator, and one of the main advocators of the Programme in the country. In the past couple of years, the Programme has reached more than 400 students annually, in six different schools, fostering solidarity and mutual understanding among children from different religious, ethnic and cultural backgrounds.

Two decades after the end of a long-lasting violent conflict, Ms. Salihspahić understands the importance of values-based education as a driving force to bring about interfaith and intercultural cooperation and learning in a country where segregation continues to be part of the every-day life.

One example of the residues of the conflict is “Two schools under one roof”, a system where children from different ethnic groups attend the same school building but have different curricula, use a similar but different term language and even attend school at different schedules, or use separated stairways and facilities. In such a system, children receive contrasting kinds of education. These practices, still present at some schools, instill division and ethnic prejudice, and hinder reconciliation.

It is in this context that Ms. Salihspahić has been working to generate dialogue and understanding within the educational system. A mother of three sons, Ms. Salihspahić can grasp the urgency of addressing the issues of violence and segregation to improve the lives of children in the country and contribute to a peaceful future.

Ms. Salihspahić is originally from Veliko Čajnu, Visoko, Bosnia and Herzegovina. She is a professor of Islamic sciences and a professor of pedagogy. She worked as a muallima (Arabic for teacher) at the Medžlis Islamic community in Gračanica, and as a professor in the Islamic high school “Osman ef. Redžović”. She is currently a pedagogue at the Musa Ćazim Ćatić primary school in Veliko Čajno. She is also among the first generation of students of a Master’s degree in “Inter-religious Dialogue and Peace Building”, and she is the President of the Mozaik Women’s Association for Interreligious Dialogue in Family and Society in Veliko Čajno.

1- Tell us about your journey with Learning to Live Together.

Through my community activism, I had the opportunity to meet many people whose work aligns closely with my own values. In 2012 I was invited to a one-day seminar in Sarajevo where I met Marta Palma, GNRC Coordinator for Europe at the time, who introduced us to the LTLT Programme. The principles and themes of the Programme were very close to my values, so I decided to get further acquainted with it, as well as with the topic of ethics education for children.

In 2012, I attended a basic workshop on the LTLT, followed by an advanced workshop. Two years later, I organized a regional basic workshop and advanced training on the LTLT for members of the GNRC from Serbia, Spain, Portugal, Montenegro, Romania, Moldova, and Croatia, and teachers from Bosnia and Herzegovina.

I used the LTLT in workshops with children to mark important dates, such as 21 September, the International Day of Peace; 17 October, the International Day for the Eradication of Poverty, and 20 November, the Day of Prayer and Action for Children. This helped promote ethics education in the schools and drew teachers’ attention to the use of the LTLT Programme with children.

In September 2018, in cooperation with Arigatou International Geneva, we organized a Facilitator Training Workshop on the LTLT for 22 participants, including teachers, community activists, representatives of the non-governmental sector, religious communities, and youth. We intended to create a network of people who would use the LTLT methodology in their work.

Learning to Live Together Facilitator Training Workshop in Sarajevo (2018)

Learning to Live Together Facilitator Training Workshop in Sarajevo (2018)

2- What do you think were the main learnings from participants?

The participants form this training workshop were from different organizations and were formally or informally working with children. It was interesting to note that, regardless of the organization from which they came, the participants wanted to master the LTLT methodology. One of the strengths of the training was the exchange of experiences through workshops and through discussing the topic of ethics education.

Educators mentioned bullying, peer-to-peer pressure, and violence in the family as a child-rearing practice, and growing in a post-conflict society influencing how children interact with each other, as some of the main challenges faced by society.

3- What other issues are you trying to tackle by introducing the LTLT in B&H?

We want to contribute to reducing violence among children, and to promote the recognition that our differences can be used as a resource for joint action and can help to improve our children’s development.

4- How is LTLT a valuable tool for teachers and what do you think can be the benefit of introducing it in schools?

The LTLT Programme is a very valuable tool for teachers who work with children because it helps children become acquainted with their qualities and strengths, to understand differences as an advantage in building relationships and supporting each other to overcome obstacles. It helps teachers to strengthen their confidence in students and encourages them to participate actively in their work.

The Programme has a very strong peace dimension which, in the period of growing up, is important for overcoming negative emotions when one may have different values and views from other people. The LTLT has clearly defined goals that guide students in the development of a positive personality.

Ms. Salihspahić, at the GNRC Fifth Forum in Panama, together with two children from the GNRC, and Ms. Saydoon Nisa Sayed, and Ms. Amina Zvonimira Jakic, both LTLT Trainers from South Africa and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Ms. Salihspahić, at the GNRC Fifth Forum in Panama, together with two children from the GNRC, and Ms. Saydoon Nisa Sayed, and Ms. Amina Zvonimira Jakic, both LTLT Trainers from South Africa and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Ms. Salihspahić and her colleagues have made child participation a priority, fostering critical thinking and leadership skills among their students, obtaining remarkable results.

After implementing the Programme with children, some of them were invited to participate in a Facilitator Training Workshop, along with teachers, psychologists, and sociologists, to be equipped to carry out ethics education programs with children. This is the case of Asja and Lamija, two youth leaders from Mozaik who have been very active in carrying out LTLT activities with other children. Furthermore, they have participated in various activities organized by Arigatou International and the GNRC.

Since becoming a facilitator of the LTLT back in 2018, Asja (17) has participated in different activities organized by Arigatou International related to ethics education and interfaith collaboration. These include the World Day for Prayer and Action, and the Global Campaign “Faith in Action for Children,” in which she sends a message to support children and youth during the Covid-19 Pandemic. She has also implemented the Programme with children.

“It is an honor for me to be able to help children in any way possible and to protect children’s rights, because if young people like me can do anything to promote good, then it is to help the once that may change the world one day, but together!” stated Asja.

Lamija (19), also participated in “Faith in Action for Children,” by sending a video message. Before that, she was invited to Geneva, Switzerland to deliver a speech at the launch of “Faith and Children’s Rights: A Multi-religious Study on the Convention on the Rights of the Child.” In her speech, she provided recommendations to bring the Study into action, and identified ways to strengthen interfaith collaborations in her community, particularly between Muslims and Christians, as part of the efforts of building cohesion in societies after the conflict.

“This study can help us to connect with our religious leaders. It encourages us to advocate for our rights in our schools, to raise awareness through workshops -for example- and to report when our rights are violated. It helps us to know that we are not alone in all of this and that we have someone to rely on”, said Lamija.

We thank Ms. Salihspahić for conceding us this interview, and for her outstanding leadership in promoting quality education for children and youth with the support of GNRC and the Mozaik Women’s Association for Interreligious Dialogue in Family and Society in Veliko Čajno. Her efforts have made a difference in the lives of many children in her country, and her work is an active contribution to bring about peace.

Mr. Hironari Miyamoto, Manager of Headquarters Operations at Arigatou International, together with Ms. Ismeta Salihspahić and Ms. Lamija Hasimovic, at the launch of Faith and Children’s Rights: A Multi-religious Study on the Convention on the Rights of the Child, in Geneva, Switzerland.

Mr. Hironari Miyamoto, Manager of Headquarters Operations at Arigatou International, together with Ms. Ismeta Salihspahić and Ms. Lamija Hasimovic, at the launch of Faith and Children’s Rights: A Multi-religious Study on the Convention on the Rights of the Child, in Geneva, Switzerland.

The post Countering Segregation Through Values-based Education in Bosnia and Herzegovina appeared first on Ethics Education for Children.

11/12/2019 - Learning to Live Together Programme implemented in 30 schools in Kenya, as part of a peacebuilding intervention

Since May 2019, teachers in the counties of Baringo and Elgeyo-Marakwet, in Kenya, have been systematically implementing the Learning to Live Together Programme among students from 30 schools, following the Teachers Activity Book developed for the implementation process.

This is the outcome of the 4-days Facilitator Training Workshop help in April 2019, for 64 teachers on the use of the LTLT Programme. The workshop was organized by World Vision Kenya, and KNATCOM, with the technical support of Arigatou International – Geneva.

The implementation of the LTLT programme was aimed to promote healthy relations and peaceful coexistence among students and members of the community at large; by creating opportunities to appreciate diversity, identify non-violent solutions to conflicts, and build on commonalities.

The implementation of the LTLT programme was aimed to promote healthy relations and peaceful coexistence among students and members of the community at large; by creating opportunities to appreciate diversity, identify non-violent solutions to conflicts, and build on commonalities.

The Programme in the 30 schools started with sensitization sessions for both teachers and students and went further involving parents and other individuals from the community who were invited to share experiences and narrate stories to children.

According to the facilitators, outdoor activities attracted community members and prompted them to appreciate harmonious coexistence and diversity. The community members also supported the Programme by providing locally available materials.

The target counties have experienced, in the past, violent conflicts with a displacement of people, loss of property, livelihoods, and even resulting in casualties. The implementation of the LTLT Programme is part of an intervention coordinated by the Kenya National Commission for UNESCO (KNATCOM) in collaboration with World Vision Kenya and Arigatou International, which aims to address these issues.

The intervention comprises three steps: Sensitization of headteachers from 30 primary schools in Baringo County, followed by a Facilitators Training Workshop for teachers on the Learning to Live Together Programme, as well as working with community leaders on intercultural dialogue, peaceful co-existence and resolution of conflicts.

Teachers reported that the LTLT Programme has had a positive impact on children, who have developed a better attitude towards neighboring communities, as well as better dialogue and negotiation skills. The Programme has promoted a spirit or living together, respecting one another in different denominations and ethnic groups, and it has also boosted the teacher-pupil relationship.

The Learning to Live Together Programme was first introduced to the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (MoEST) of Kenya in 2014. Soon after, a pilot program was carried out in 13 schools, reaching 657 children from the Tana River County, an area heavily affected by inter-ethnic violence. The implementation of the Programme showed positive results in students, and teachers, as well as in the overall community.

Arigatou International Geneva and its partners: World Vision International, the Kenya National Commission for UNESCO, and the Ministry of Education are pleased to see the level of commitment after the workshop, including continuous implementation, reflection, and documentation of the process. Partners are in discussions to organize a second facilitator training workshop to continue supporting the teachers.

The post Learning to Live Together Programme implemented in 30 schools in Kenya, as part of a peacebuilding intervention appeared first on Ethics Education for Children.

04/07/2019 - Promoting Learning to Live Together in Latin America and The Caribbean – A Story of Service and Conviction

Ms. Mercedes Román has been a key driving force in the implementation and dissemination of the Learning to Live Together Programme in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) since before it’s conception. She was part of the first group of experts, gathered by Arigatou International in 1998, to work on the launch of the Global Network of Religions for Children (GNRC), and has been working with Arigatou International ever since.

As GNRC Coordinator for Latin America, she conducted several test workshops in the region to try out what was then known as the Ethics Education Toolkit. After the launch of Learning to Live Together, she has conducted countless Facilitator Training Workshops in the region, as well as Europe.

Ms. Román has dedicated her life-work to serve the most vulnerable in our society, and to promote the rights of the child, to contribute to their full and sound development. Nowadays, she is the Senior Advisor for the GNRC in LAC and is also part of the group of experts working in the adaptation of the Learning to Live Together Programme to middle childhood years.

In this interview, she shares about her journey working with children and women in vulnerable situations, and how her family and religious background instilled in her a strong sense of justice, generosity and caring for the most needed members of society.

Ms. Mercedes Román, (fourth from right to left) together with other members of the first Interfaith Council on Ethics Education.

Ms. Mercedes Román, (fourth from right to left) together with other members of the first Interfaith Council on Ethics Education.

- Please, tell us about yourself and your journey working for the rights and wellbeing of children.

I was born in Ecuador and until I was 18 years old I lived in my hometown, Latacunga, a provincial capital very quiet by then, with very strong family and social relationships. I grew up in an extended family, with a lot of protection and a natural sense of caring for others. I am the oldest of 4 siblings, my father instilled a strong sense of justice, and my mother was an example of generosity. The person with the greatest influence in my childhood and adolescence was my maternal grandmother, a very devoted Catholic practitioner, caring and proud of her 33 grandchildren.

The Sisters of Charity in my Catholic school, when I was 8 years old, motivated us to participate in the Luisa de Marillac Congregation, whose mission was to assist the poor and the elderly. In addition to carrying out collects for the poor in the city, we had to visit an elderly person; mine was Eloisa, she was very poor and in a delicate state of health, and I still have memories of my visits to her in the hospital. This was a great lesson of life for me, I learned that caring for the most vulnerable goes beyond material help, and I experienced that helping the poorest and most needed made me happy. I was very young to understand poverty as a socio-structural problem, but this understanding was developed and that is how I decided to study Sociology. I also obtained a diploma in Anthropology and studied Philosophy for three years.

My calling to work for the socially most vulnerable was born in a Catholic context, and that core of religiosity and social concern always remained. I started working as a university student, and all my labor has maintained that core; my first job was with the Christian Family Movement, the second in Church and Society for Latin America, which was an ecumenical organization. Later and for 22 years, my husband and I were Maryknoll missionaries, a Catholic institution that emphasizes in its mission a preferential option for the poor.

With Maryknoll, my first mission was with the Ecumenical Commission for Human Rights in Ecuador, on the rights of women from very poor neighborhoods. Some of them were illiterate, but for me, they were a “second university”. Working with them on the relationship between mothers and children, violence against children and children’s needs were unveiled for me as a social problem of great magnitude. After working for 6 years with poor and abused women, they were the ones who told me: “… we understood, and we see ourselves as people with rights, but somethings (it) may be too late for us, work for the children”, and I did. With a small donation and the collaboration of friends and people working for children, in 1987 we officially founded the Ecuadorian Section for the Defense for Children International (DCI). DCI-Ecuador was a pioneer in the investigation and reporting of the sexual abuse of children, a concern that was born in my work with women. My work for the rights of women was unfolded in the work for the rights of children.

I had the privilege of enrolling with DCI in the years of drafting, adoption, and promotion of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, and for this, I worked first from Ecuador and then from New York, as Permanent Representative of DCI in the UN and UNICEF. Later, I held the same representation for the Maryknoll Global Affairs Office. In the midst of these two representations I worked 3 years in Paraíba, Brazil with the Pastoral for Minors, also in the field of prevention of sexual abuse of children.

- When did you first get engaged with Arigatou International, the GNRC, and the Learning to Live Together Programme?

It was at the end of my term in Brazil, in 1998, when the Arigatou Foundation invited me to be part of the working committee to prepare for the launch of the GNRC, which took place in 2000 at its First Forum. This proposal of interreligious dialogue in favor of children at the global level was both very attractive and very challenging. The first certainty of the committee was to make explicit that the GNRC framework would be the Convention on the Rights of the Child. Once the GNRC was officially created, it was necessary to concretize its mission in programmatic proposals. This is how the Ethics Education initiative came about with an office in Geneva. In the Second Forum of the GNRC (2004) this initiative was officially launched, and after 4 years of work, in the Third Forum of the GNRC (2008) Learning to Live Together (LTLT) was launched, as a practical pedagogical tool to work on ethics education with children.

- What was your role during the development and testing of the Learning to Live Together Programme?

Until 2015 I was the GNRC Coordinator for LAC, and as such, I participated in the preparatory work of the LTLT manual. At the same time in LAC, the interreligious dialogue proposal of the GNRC in favor of children was set up at the country level through interreligious committees. From these committees, the implementation of LTLT has been possible, starting in 2005 with 4 pilot workshops (in Colombia, Ecuador, El Salvador, and Panama), prior to the edition of the Manual. Then came the most complicated task: the implementation that, as it is conceived in the Programme, begins with training workshops for people who work with children, both in formal and informal education. In LAC, around 32 training workshops have been delivered, to people working in informal education settings, teachers working in religious schools, and after-school programs for children from religious institutions. People from 16 countries participated in these workshops. Many of the activities suggested in the manual, and a good portion of how the training workshops are now structured emerged from the workshops at LAC.

Ms. Mercedes Román at a Facilitator Training Workshop in Ecuador, in 2007.

Ms. Mercedes Román at a Facilitator Training Workshop in Ecuador, in 2007.

- After so many years of being involved with Learning to Live Together, what do you think is its main contribution to the society in LAC?

The GNRC, as it is conceived, is a network that depends on the collaboration of other religious institutions, but what the GNRC has to offer is the Ethical Education program, with LTLT as a concrete instrument to work with children, which is an offer in demand. Like many, I think that global problems, violence in its various forms, starting with poverty and social inequality, and going through ecological destruction, are ethical problems. The economic resources worldwide are growing, but poverty, social and ecological violence are not resolved, due to a lack of ethics in the political work. Children are nourished by this violent and destructive culture, which is why it is urgent to introduce new ethical visions into their education, participating from an early age in actions based on ethical values, building a culture of peace, which is the proposal of LTLT.

- Can you share with us a story on the impact of the Programme?

The impact of socio-educational programs aims at personal changes of attitudes, which in itself is very difficult to measure; the changes of human visions are largely intangible, and concrete collective actions from the children themselves, as a result of new ethical attitudes, is only one measure. In addition, the training given can be deployed in unforeseen ways and actions that are impossible to monitor. Here, two examples of concrete cases of impact of LTLT, the two have to do with Ecuador but are intertwined with other countries in the region. The first case has monitoring possibilities, for the second we have only informal and casual information.

Maribel León, an Ecuadorian teacher, received LTLT training while working as a missionary in Guatemala. Back in her country, she has been implementing LTLT in the Catholic school where she works with teenage students. A concrete impact of her work is the commitment of the young adolescents that received LTLT, who work, in turn, with young children, within the values program of the School. This is a feasible case of monitoring and evaluation.

Ismenia Íñiguez, as a UNESCO-Ecuador official, collaborated and participated in one of the training workshops delivered in this country. Years later, UNESCO Peru hired her to prepare teaching support material on non-discrimination and culture of peace; and, later, for an educational innovation project in the District of San Marcos, a Quechua-speaking indigenous area of Peru. In a casual conversation, Ismenia reported that she used LTLT material and teacher training in San Marcos. She shared with me the material she wrote and Arigatou is credited there. This is an unpredictable impact at the time of the first training and was not subject to monitoring or evaluation.

Ms. Mercedes Román at the Expert’s Meeting for the Adaptation of the Learning to Live Together Programme to Middle Years, in Switzerland, in 2018.

Ms. Mercedes Román at the Expert’s Meeting for the Adaptation of the Learning to Live Together Programme to Middle Years, in Switzerland, in 2018.

- What recommendations do you have for Learning to Live Together to respond to the new needs and challenges in Latin American societies?

One obstacle to introducing LTLT in the public education system in LAC is the religious connotation on the cover of the manual; the phrase “an interreligious program” closes doors in the public schools of the region, which constitute the majority and the ones with more needs in the area of values. The public education authorities ensure the secular tradition of this sector with great zeal. Without changing the contents of LTLT, it would walk easier into all kinds of education if the interculturality and inter-religiosity of its proposal and contents were an explanation immerse in the introduction of the manual, as a tool for working with children that adapts to different contexts.

- Ten years on, ¿what challenges and opportunities do you see for Learning to Live Together in LAC?

Among the religious institutions of LAC, the GNRC is known as the organization that implements Ethical Education and the Day of Prayer and Action, being the first where the greatest efforts have been made. In spite of this, in terms of impact, LTLT as a program confronts problems in the sustainability of its implementation, since there are no on-site human resources to support and monitor such implementation. Those who are trained leave the workshops very motivated but need more support in the implementation from their own institutions and from the program itself.

LTLT is designed for children between the ages of 12 to 18, but parents and educators perceive that nowadays children in these ages are already independent regarding the information that influences the formation of their values. Some educators have started on their own to adapt LTLT for younger children. Given this fact, the new efforts of the office in Geneva to offer materials for children from 6 to 12 years old within the conception of LTLT is very important.

We thank Ms. Román for conceding us this interview. Her life-long service is an inspiration to those working on building a more just and peaceful society for the wellbeing of children.

The post Promoting Learning to Live Together in Latin America and The Caribbean – A Story of Service and Conviction appeared first on Ethics Education for Children.

03/12/2018 - Tackling Bullying and Violence in Schools Through Value-based Education in Indonesia

The Learning to Live Together Programme (LTLT) was first introduced to Indonesia during a facilitator training workshop conducted by GNRC South Asia and Arigatou International – Geneva, in partnership with the Indonesian National Commission for UNESCO in 2012 and with the help of Ms. Wati Wardani and Mr. Fendra Kusmani. Since then, it has reached more than 1,000 children in more than 30 schools in the country.

Ms. Wati Wardani lives in Jakarta, with her husband and four children. She is currently the Country Coordinator of Generation Global, the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, and has been a facilitator of the Learning to Live Together Programme for several years. In 2017, she was invited to participate in a 5-days Training of Trainers workshop in Annecy, France, where she became an Official Trainer of the Programme.

Four Facilitator Training Workshops have been conducted in Indonesia during the past four years, reaching almost 100 teachers from kindergarten, elementary, and junior high school levels.

What are the main issues affecting children in these schools, and how has the Programme contributed to tackling these issues?

Bullying and violence at school have been the main issues faced by the students across the different schools, but most teachers and educators in the country lack the institutional support to gain skills and knowledge to help them tackle these problems. Many teachers said that they knew the issues brought on the training – peace, respect, tolerance- but didn’t know exactly how to deal with them with their students.

What transformations have you been able to see in students and teachers?

After the implementation, teachers have reported that students were able to construct a sense of togetherness and awareness about friends, family, and others; increase their sense of respect and empathy across divides, and transform their mindset to become agents of change.

Many teachers have said that they were aware of the issues brought up in the training—peace, respect, tolerance—but didn’t know exactly how to deal with them with their students:

“I know bullying and lack of respect is around the schools but I didn’t know what to do, other than telling the students not to do this or that. The training has opened my mind on how simple it is to bring a positive impact using the methods and techniques from LTLT.” –Teacher

“The LTLT training has transformed me to be a better teacher. I always remember to create a safe environment for my students to learn and explore their potentials’. –Teacher

“As a kindergarten teacher, I have tried to adapt LTLT techniques to fit my students’ ability. More importantly, I’m more aware of teaching values that LTLT promotes–respect, empathy, responsibility–and to create a dialog between me and the students, and among the students.” –Teacher

What do you think is the added value of the Learning to Live Together Programme for Indonesian society?

Schools are looking for ways to teach values, particularly, related to the current issues – lack of respect, intolerance. LTLT is about teaching that values with its new pedagogical approach.

What are your plans regarding the LTLT in Indonesia for the future?

We are excitedly waiting for the translation of the LTLT manual to Indonesian. Having the manual translated into our language will allow us to further train facilitators/teachers of elementary schools in different parts of the country.

The post Tackling Bullying and Violence in Schools Through Value-based Education in Indonesia appeared first on Ethics Education for Children.

21/03/2018 - The Enriching Journey of Two Young People to Create a Peaceful Society in Tanzania

“In 2007 at Azania Secondary School, I overhead from my classmates about the Peace Club initiative at school. “Peace?” I asked, not sure why I was intrigued, but after one meeting I became overly interested in the idea to take an active peacebuilding role.” This is how Yusuph Masanja, Coordinator of GNRC (Global Network of Religions) Tanzania, describes his first contact with the GNRC Peace Clubs. Since then, he has stayed on the front line advocating for the GNRC mission.

The road taken by Clara Mduma was quite similar. Clara joined GNRC Tanzania in 2004 when she was only 14 years old. Two years later she participated in the first international workshop organized by Arigatou International in Geneva to test the initial idea of the Learning to Live Together Programme.

Taking part in Learning to Live Together activities enabled her to understand her responsibilities in her community and to mobilize children and youth. In 2008, she assembled her class and all Peace Clubs in Dar es Salaam to write a paper about the objectives that children wanted to add to the Child Act Bill, which was being discussed at the moment. This influenced the government to organize a meeting to collect the children’s views before the Child Act Bill was passed into law in 2009.

After completing her studies and while she was working for Art Against Poverty, (a program for youth coming from vulnerable backgrounds), and volunteering to introduce clown therapy for children at a hospital, she participated in a Training Workshop to become a Facilitator of the Learning to Live Together Programme. Later in 2017, she became an official Learning to Live Together Trainer.

In this interview we talked with this two outstanding young adults, who were raised in the Peace Club ecosystem, learning about responsibility, empathy, and respect at a young age, and working hard for youth participation, the rights of the child and peacebuilding in Tanzania.

1- Clara, how has the Learning to Live together influence your upbringing?